Please like, share & subscribe! Patreon coming soon!

SUPPORT THE ARTS! Thank you for your interest in maritime literature and other multimedia ventures on the high and low seas!

I felt a crack.

Something fractured.

Like a fault line in my brain.

Or my tiny idealist heart shattering.

My sailing trip is now basically over. I said I wanted to test the boat in the harshest conditions both she and I could handle coastal, in winter, to see what we were capable of. I lived on the edges of the sea and my nervous system for seven months exploring from Maine to Maryland. I never had a plan. The boat was completely unfinished and barely hospitable. It was very cold. I was practicing seafaring. She was half seaworthy half dilapidated.

Things were starting to get to me under the current conditions, but it always all seemed to work out in the end. The boat and I came right up on our edge—of heavy weather, and I of my own mind.

Suddenly I more or less now know what my days will look like. I have a plan. My work is steady, the boat patiently waits for her refit which I can now slowly begin. The amenities are plentiful. The people are, fine. And yet I can’t help but feel like I’ve lost something.

Magic.

For a while everything was really magical. All my dreams were coming true. There were ups and downs but overall, I felt this cosmic thread connecting my every move towards something larger and greater than myself. I was on the right path with my single handing, my career, my personal life and relationships. And everything around me physically reflected that.

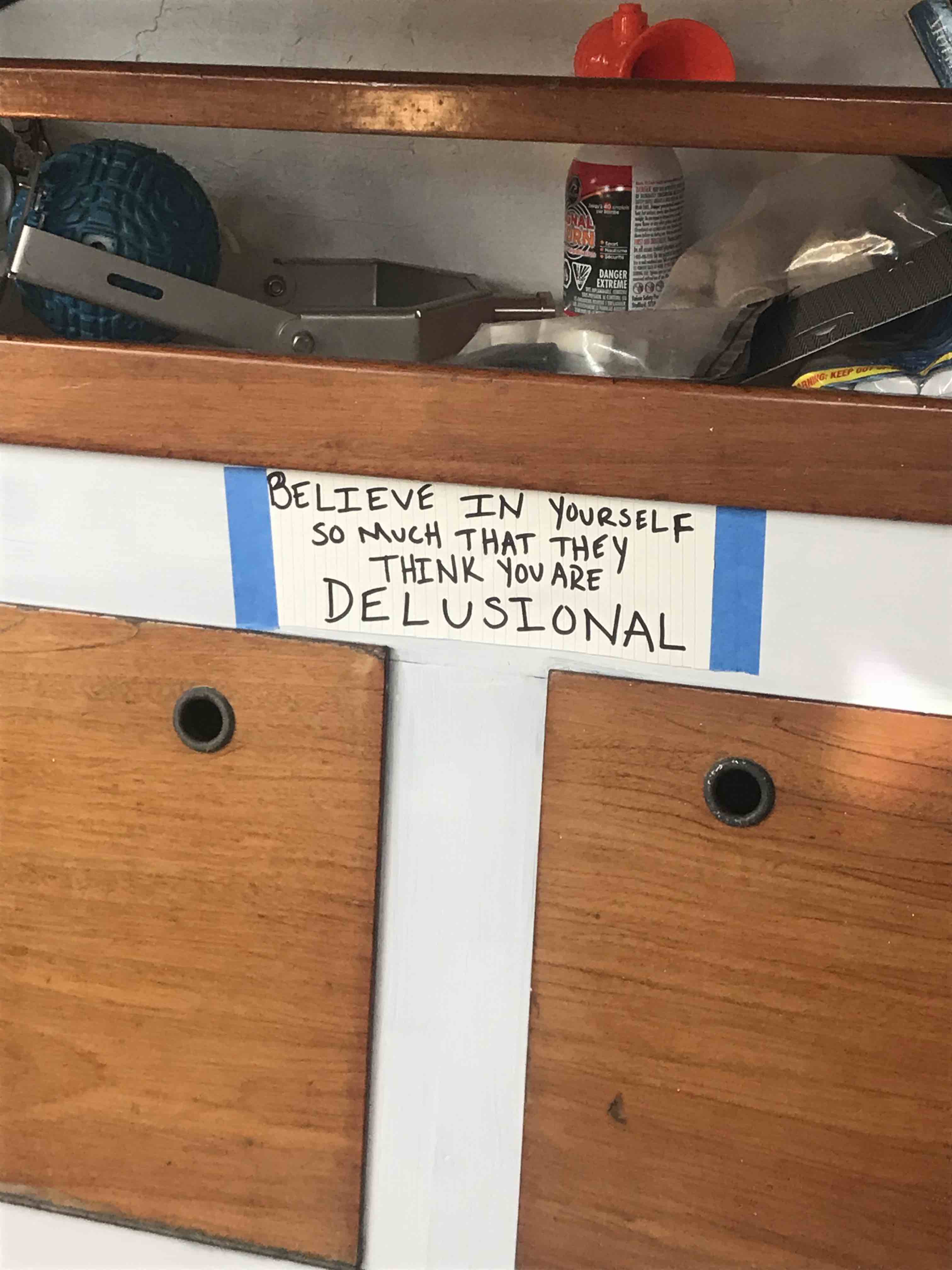

This mindset took a long time to achieve and has not been without its regressions. In an attempt to break from self destructive tendencies and crippling self doubt I put notes all over the hull of my new boat with positive affirmations and coping mechanisms, to gain control of my mind and life.

It worked. But did it go too far?

One of the notes read: “Believe in yourself so much they think you are delusional.”

When you continuously have fated, innately romantic and profoundly passionate experiences in regard to every single facet of your life you start to wonder if perhaps the depth of your being and feeling is not magic at all, but a fault in your own wiring that makes you unfit for modern society and relationships.

I’ve often asked the question: do two people fall in love, or does love already exist and two people fall into it? This is a matter of idealism vs. materialism. In philosophy, idealism states that ideas create your material reality. In materialism it’s the material reality that creates ideas.

I am at odds with the material world.

This was apparent when I sailed my unfinished boat and paddled a poorly repaired kayak alone through New York City. Staring at the buildings with a pink sunset and the ocean in front of me it truly baffled me how I was literally the only one out there out of all those millions.

Soul mates. Death pacts. Planets and stars aligned. Astrology. Tarot. Sea witchery. I believed that all my boats had lead me here to this current boat and was symbolic of the spirit of sailing and adventure. That I’d done well in my travels. My dead friends were living on everywhere around me; In my books they gave me, the money they left me, the sea, and through smell. My living friends were serving as inspiration. I felt that despite my mistakes and wrong turns or perceived losses at the times—they all needed to happen so I could be as solid and focused on the dream and goal as I now am. Or, was…

“Do other people just not get to have this?” I asked my old friend Capt. Dan who was the first person to teach me about engineless sailing. “Not only do they not experience it, but they don’t even know it exists.”

I was this close to signing up for a subscription based predictive astrology service. Everything was meant to be and I was moving along with my life’s plans. And then I made a terrible mistake. I started researching. Scientifically, magic doesn’t exist. Only the mind’s ability to believe and perceive it. Science calls this magical thinking vs. the belief in magic. Magical thinking is more of an evolutionary adaptation of the human brain, perhaps in order to survive trying times… Magical thinking is proven to have cognitive and creative benefits. The actual belief in magic, however, has real world implication and historically lead people to cult like and political terrorist behavior, as well as isolation and individualism.

It seems I had fallen into a bit of a rabbit hole.

In one study they used questions such as “to what extent does the ocean have consciousness,” as a quantitative element of how to measure magical belief. It’s no wonder I got swept away living so close to the sea. It’s the only way I know how to survive. If you take away my belief or faith in a person, or a boat, or myself —it stops existing. So who is to say magic doesn’t exist, so much as I’m the one in control of its existence?

I’ve always said that boats are greater than the sum of their parts. How something so simple can be capable of driving something so complex— an adventure through the natural, social, and inner world. Maybe that’s why I do it, because the sea is closest thing to magic I could find.

SUPPORT THE ARTS! Thank you for your interest in maritime literature and other multimedia ventures on the high and low seas!

Welcome all of us to the new age, new year! Wow, 2022 really has felt like a fucking fully loaded winch handle to the face if you know what I mean! And we’re off!

I’m not kidding. I’ve been crying for literally two weeks straight. I cried so much it felt and looked like I’d been punched in the face. I googled it and sure enough my tears had given me two black eyes.

My grandfather died. I witnessed lifelong bonds fracture. A profound personal and professional connection I’d built over a year with an important figure vanished in one night. All within the last month. Nothing makes sense. I am psychologically changed.

But that’s another story.

Do people still need those? Stories? Now more than ever, perhaps. Two years into a pandemic. I think sailors have always been relatable. The sea has always been compared to difficult times in life. Difficult emotions. The ship a metaphor for getting through them.

But what about getting through difficult times and difficult emotions, at and on the fringes of the sea?

I’ve always had this tendency toward the extreme. My parents kept control of me enough when I was a kid that I never ended up on the streets, only the road. The blue road. Never home-less. But home-free. And, eventually, finding home on the sea. But I didn’t chose sailing. I had an opportunity to be out at sea once and from then on nothing else would suffice.

For years I tried to build a home on the sea aboard a broken boat—and finally learned my lessons. I can’t say the same for love—I still try and build a home in broken hearts.

For many people, not only sailors, the sea is home. The problem is we can’t live there. So we settle for boats. Surfboards. Seaside cities. Summers at the beach.

I’ve been studying single-handers for a while now. The ocean sailing kind. Their boats, books, and films. Somewhere along the way I broke this third wall. My heros became something else entirely. Something real. Something tangible. And it wasn’t always pretty.

Something else happened. I became someone else’s hero. More than once, and, I disappointed them. So what should I have expected from mine?

I need to make sure I’m not trying to go further out to sea for the wrong reasons. I have to make sure that I’m not trying to go further out to sea in order to love myself, but that I love myself enough to go further out to sea. That I love myself to keep going. To not give up. To remember that it’s up to me and my boat. No one is coming. You have to go after your dreams yourself. I don’t know why. It seems against human nature.

The sea is the only place that calls of romance without the need for another person. It is something I have gotten to know intimately. I try to remember, even on anchor, that I sleep with the ancient wisdom of the sea beneath me, and that means I’m never really alone. I can’t forget that.

I’m getting to know the sea better. The wind. Myself. I recently felt my sense of self become somewhat fragmented. My emotional self, and my conscious self, separated. It was the result of what I can only imagine has been the constant, hyper vigilance needed for life on the fringes of and at sea.

It didn’t take long before I was back on land and that changed, as I became entrenched in and witness to relational conflict. I didn’t lose my hyper vigilance, I just lost my sense of peace that came with it.

In many ways I want to be alone at sea. Well, I want to be able to be alone at sea. I have to be. It’s the only way I feel I can be a competent sailor. Because doing it alone is better than not doing it at all.

I chose a life at sea to avoid heartache and attachment someone said to me—but I like to think I choose life at sea in spite of it. Because it seems that boats, and boys, break my heart.

But never the sea.

The sea just tries to stop it.

###

If you’re new here or checking in wondering where I’ve been. You can catch up here!

https://www.sailmagazine.com/author/emily-greenberg

https://towndock.net/search/?q=Emily+greenberg

https://www.sailmagazine.com/cruising/enabling-a-low-budget-boat-flipper

Keep an eye out for some of my work forthcoming in Spinsheet Magazine, SAIL magazine, and towndock.net . The story is always free here and on @instagram!

If you enjoy my content please consider a donation as this takes hours to write, shoot, edit, upload, and more.

Standby for the forthcoming LONELY BLUE HIGHWAY : A Docu-SEA-ries, AND MORE!

PLEASE Check out and SHARE my VIDEOS!!!! DINGHY DREAMS IS NOW ON YOUTUBE!!! LIKE AND SUBSCRIBE on Youtube! This is a grassroots, video diary of a seapunk. This video series is edited by renowned Seattle/NY based editor Whitney Bashaw. Support the arts! Patreon page coming soon…

When I think of the East Coast the first thing that comes to mind is not a wild landscape. Yes, there are beautiful ocean beaches, historic lighthouses, protected national seashores, and a variety of other delights ashore. But the majority of shoreline is privately owned. I think of the east coast as the place I grew up. A good place to buy, fix, and practice seafaring aboard small sailboats. As a place you have to sail past to get to the islands. But never as a place to travel to. It is not the land in itself that interests me. It is the sea. It is being out of sight of land.

Coming back to shore here is merely a means to an end as my boat is a continuous work in progress, not quite ready to be at sea for longer than a few days. It is distant landfalls with far less population that intrigue me, not the coastal U.S. cities. Sometimes I wait weeks for a small passage window, anchored in some town I’d never chose to visit on purpose. Where there are few public landings and grocery stores are miles outside of town down four lane highways. Sometimes I get lucky and I can see a rail yard from the lawn of the public library and watch freight trains roll by while using the WiFi. Other times, there are mates around. I’ve been up and down this coast enough to have friends almost wherever I go, but not always.

From sea the coastline can look almost perverse. The abandoned Ferris wheels of the New Jersey Coast, the sky scraping condos of Miami Beach, accompanying tributaries marked endlessly by mansions, water towers, beach houses, second, third, and fourth homes. It’s as if the only reason they stopped building is because they ran out of land. They ran into the water. It like civilization is just perched precariously and ready to crumble into the ocean. Like an apocalyptic daydream.

The wind can be a challenge as well.

The East Coast is killing my soul a little.

But I do it for you, Atlantic.

[email-subscribers-form id=”1″]

Where do you find the heart of sailing? Is it witnessing both a sunset and a sunrise at sea? Is it in a boatyard with no fresh water, skin itchy with fiberglass? Is it in stepping ashore after a long passage, and drinking sparkling water with a lemon you foraged next to an abandoned dock? Is it in being wet, cold, and slightly frightened?

Or Is it found somewhere else? Is it found in yacht clubs and private marinas? Is it found in a fully enclosed cockpits with electric winches? Or in that moment you cash in your stocks and buy a boat to sail off into the promised sunset, cocktail in hand?

In the harbor right now there are three boats, including myself, that are all “basically engineless.” Meaning we all have some kind of auxiliary propulsion that only really work under totally calm wind, wave, and current conditions. Whether it be an extremely underpowered 2.3 HP outboard, or an outboard with a shaft that isn’t long enough, or a dinghy hip tied. That means in any and almost all conditions we are sailing, unless it’s for some short stretches of the ICW.

Is it because we are broke? Young? Idealists? Perhaps a combination of all three.

I’ve been a vagabond since I was 22 and bought my first boat at 26. I’m 31 now. I haven’t paid rent, except for the odd slip at a marina here and there for a few months at a time, in ten years, and have held various jobs. I happened upon sailing by chance on a yacht delivery in New Zealand and sailed across a literal sea a thousand miles over ten days, and I’ve just been trying to get back to that ever since, on my own boat.

But I never felt stuck in life, in a career, or in the throngs of capitalism that so many people feel that leads them to quitting their jobs and searching for boats. I’ve felt stuck with no money and very unseaworthy boats, but I didn’t do what most of my generation did; which is basically get real jobs. And now that they’re in their thirties and sick of the grind they’re like, let’s get a boat.

And they go buy some plastic boat from the eighties with a comfortable interior and no inherent seaworthiness in its design, but it’s safe enough. They focus on having a good engine, and then motor across the Gulf Stream to the Bahamas. They follow the “Thornless Path” and motor sail in the calms that can be found in between the prevailing opposing winds. Until they eventually reach the Caribbean and it’s all downwind from there. They have enough money, and enough confidence, even never having never sailed before, that they make it just fine.

Lots of people do this, especially with the advent of YouTube. People are like, “Yo, I can live on a boat and make a YouTube channel to pay for it?!”

But I can tell you this is not where you will find the heart of sailing. That is something you really have to look for. This is where you will find a departure from it. I’ve been trying to find it for years by now of living aboard and messing around with boats, and I still know nothing. “Remember you know nothing,” an old schooner captain told me. That’s what makes you a good sailor, he said. A good captain.

Famous sailor Nancy Griffith said, “know the limitations of your crew and your boat.” Crew, for the most part, has usually been only me. And I’ve scrutinized both myself and my boats heavily when weighing certain passages. I worked at marinas as a way into even learning about boats. My first boat I stuck to lake Champlain, my second I took down the Hudson River and to the Florida keys, only spending a little time offshore. The boat simply wasn’t prepared for passage making. Most of the offshore sailing I’d done before my current boat, was on boat deliveries. So I hold myself to that standard of seaworthiness, of what I’ve seen on the sea.

I spend more time fixing my shit to be at sea then I do actually at sea. I have to fix boats so often because I don’t have money, so I’m pretty DIY. The trouble is I really don’t trust my work. I rely on people with much more skill than I have to tell me if I’ve done something right. For me, the goal is to make my boat as safe and comfortable as possible on the sea. It’s been and continue to be arduous, refitting old boats to be sustainable in such an inhospitable environment, with little money and no formal training.

Sometimes I envy the other kinds of travelers. The backpackers. The ones who hoof it, bus it, ride planes and hop trains. But that’s not for me. Devoted to the sea. And if I can’t be there, damn it, I’ll be on land just trying to get there… because nothing else matters.

[email-subscribers-form id=”1″]

There’s a tropical storm bearing down and it’s about to clip my anchorage. I wasn’t going to write this on the internet anywhere so my parents wouldn’t worry. But they found out about it on their own accord. I’ve got two anchors out and am protected from the wind direction in this harbor. It’s not expected to blow any worse than a winter gale, but still, it’s a bit early for this nonsense. I’m further south than I’d ought to be this time of year, but I thought I only had to worry about the heat and thunderstorms the further we marched into summer. This time last year I’d just barely arrived on the Chesapeake Bay by now. Tropical Storms were the furthest thing from my mind. Sean was still three weeks out from sailing north around Hatteras. This is the time of year people sail to Bermuda and cross the Atlantic. It’s not supposed to be like this. It kind of snuck up on me without warning. Whether it was fast moving or I simply wasn’t paying attention.

This changes everything. I was planning to cruise the sounds on my way north stopping at different islands for anchorages. Taking about a week to meet up with the inland waterway and then follow that into the Chesapeake Bay. Now I’m not so sure. With the potential for tropical storms and hurricanes to become threats in a matter of a day or two notice, I’m wondering if I should seek the protection of inland waters sooner. I don’t have a large diesel engine that I can just crank on two days before a storm to guarantee miles. I’m at the mercy of the winds.

Speaking of diesel engines, I ripped the one out of this boat and sold it in a quest for simplicity and to pay for my refit efforts. I’ve sold enough gear off this boat now that I got her for $1000. And let me tell you, it’s starting to feel like a thousand dollar boat. I’ve had to redo damn near everything. Through hulls, coamings, standing rigging, chain plates, etc… etc.. I find it troubling that the only thing really of “value,” on the boat, was the diesel engine. That’s what people consider essential. It didn’t matter that the rigging was precarious and all the wood in the cockpit was rotted, or that the through hulls were a terrifying corroded mess of antiquated parts…it mattered that it had an engine you could just fire up and “go.” How far have we come from what is considered essential, and seaworthy? When did it become engine first, then rigging? How many people if you ask, what is the heart and soul of their boat, would say their inboard engine?

Sean has moved off the boat and onto his trimaran. So, I’ve effectively had this boat on my own now for one month. I bought the boat through love colored glasses and we both had dreams to fix it up together and cross the Atlantic. With him I really thought it was possible. But it turns out love isn’t always enough. I realized that I stopped wearing my harness and life jacket when Sean came aboard. I stopped caring about a lot of shit.

He’s the kind of person who can manage to fucking circumnavigate on a boat that was basically derelict when he got it. With the right amount of luck, a great deal of intelligence, and an amygdala that doesn’t register fear and risk in the same way as neurotypical people—he fixed it in mostly all the right places and transitted the fucking planet. Not only is this a feat most sailors and people will never achieve, but he did it probably in one of the most uncomfortable ways.

No bunk. No sink. No standing head room. He told me roaches used to eat his toes at night on passages. I thought he was kidding. I always used to think he was kidding. His boat was a mix between some mad scientists lab and Davy Jones’ Locker. He just laid down on a bunch of wires to go sleep before I met him. All the way across the seven seas–passing the time alone contributing source code to open CPN, a navigation program used by world cruisers, and designing and manufacturing his own auto pilots.

I should have known better than to disturb this delicate creature. Because here we are now. It’s funny how someone can go from your hero to your ex that you have petty arguments with across the harbor.

It turns out the “Go North” and the “Go Offshore” are two entirely different lists. The former I’m almost done with and the latter I plan to finish on the Chesapeake.

There’s nothing left for me here.

I’m still not sure how that story ends, so it’s a good thing the submissions deadline for my anthology project Heartwreck: Romantic Disasters at Sea, has been pushed back. More info on submission guidelines here. New deadline is TBA.

[email-subscribers-form id=”1″]

I first met my friend Jake in a boatyard on Lake Champlain while I was sitting on the rocks taking apart a trolling motor that I never would end up getting to work. He cracked open a micro brew and shouted from the ground up to another mate on their boat. Quickly after we were introduced he said to me, “You remind me of my ex wife, and that’s a compliment.”

That summer was spent as a tight knit group of sailors rendezvousing in anchorages, sailing each other’s boats, and collaboratively engineering the shit out of repairs. I can easily be brought back to that time we nearly knocked down Jake’s boat in a squall. Or ate sausages in the cockpit next to the cliffs of Kingsland Bay with his partner. Or the time he offered to help me rebed my leaking deck hardware but I abruptly called it off after we did only a few bolts because the whole task just seemed so daunting. He used to call me, “kid,” which I found annoying and would say, “dude you know we’re only like ten years apart, right?”

Jake had a Columbia 26 at the time, which he’d completely restored. He still exists in my phone as “Jake Columbia 26.” From her damaged hull to the rotten core under the mast, new roller furling sails, glassing in the old big port lights to put in smaller, more seaworthy ones. His eventual plan with the boat, other than sailing the shit out of it on Lake Champlain, was to trailer it across the country and launch it in Washington state to sail the inside passage to Alaska. But life happened, and he sold the boat. I didn’t understand it at the time, but Jake always liked to tell me, “The adventure is not your life. Your life is the adventure.”

Jake has always been there for me. Like a therapist, a mentor, an older brother from another mother, or a spirit guide. He’s helped to see me through many of sailing life’s challenges and been there to celebrate the victories as well. He is my emergency contact if there is ever a problem at sea. He literally always answers my messages and calls to the point where I’ve wondered what the hell he even does all day. He even responded once from Belize. He has helped, like any good friend therapist, to create a secure attachment that feels safe and unwavering that I’ve been able to translate that into many other relationships in my life. He has led by example on how to be a good person, a good partner, a good friend, a good ally.

Before giving up a life of dirt bag foolery for the stability of a regular job he was a lot like me. Which I guess is why, in a sense, I’m his hero.

But really, he’s mine.

One time we were sitting on my boat with our other friend, Dale. Jake had just gotten a ukulele and had begun playing it incessantly. With his eye twitching and voice about to crack, Dale turned to him and said, “PLEASE, Jake, for the love of god, would you stop playing that thing?!”

Jake laid down his weapon, hands up with a sly grin.

He’s come a long way from that annoying, repetitive strumming and has written a song so dark, so traditional, and so poignant in response to the global corona virus pandemic that I couldn’t help myself but to do my own rendition. A rendition that deeply offended my mother (sorry, mom), but did help to lift the spirits of my worried old friend.

You know shit is getting real when the person who has always been a rock to you is starting to get scared, and you’re the one reminding them that everything is going to be okay.

It has to be.

In other news: I said I wouldn’t worry about cosmetics but… Feel free to donate to my paint fund!

I’m currently northbound by train to New York on my way to see my grandfather for what could be the last time.

I imagine what I’d say after he’s gone.

“He was a great man.”

And anyone who knows him would say that. In fact, when I texted my best friend to let her know what was happening, that’s exactly what she said.

He’s a great man. Present tense. Because as I write this he is still alive.

He has the innate ability to share his love and affection equally—among all of his children, his grandchildren, my grandmother, along with many other extended family members, students, and neighbors.

I want to say it was just us that had such a special bond, but he had that with everyone.

We all felt like the favorite.

I can imagine my grandmother saying my name now, in quiet surprise to see me. “Em-au-ly,” she’d say in her German accent, like there’s a marble in her mouth.

My love for and with my grandparents is the truest and purest form of love I’ve ever had the privilege to know—unconditional and without judgment. I remember showing up at their house as a sophomore in college, reeling from my first heartbreak and prescription anxiety meds I had my first panic attack. No questions asked we just sat and looked out at the mountains.

I started to learn how to deal with anxiety naturally after that.

For most of my life they resided on top of a mountain in upstate New York with only a wood stove for heat, and an ever revolving door of dogs, cats, and the birds their feeders would bring. Even the occasional bear would grace their property.

I think that’s where I first learned about inner peace, or the act of striving towards inner peace. There was one spot on the property, a small clearing amongst greenery and moss covered stones the size of a perch.

He called it Eden.

My grandfather taught yoga right up until his kidneys started failing a few days ago. He kept up with his classes as best he could as his health deteriorated. The last class of his I took was a year ago and he no longer did the full postures. His students followed his voice while he stood there. I remember laughing during the class—he always reminded me of some ancient eastern mystic. We called him Mr. Miyagi despite his being a Brooklyn Jew. After the class I commented on how his teaching style had changed and he said, “now I just walk around like a little emperor.”

Back in my late teen years my grandfather got a gun, a six shooter I’m not sure he ever used. He’d theatrically reach for his hip to pull a gun he never actually kept there. That’s where he earned the nickname Pappy Greenbacks, a name that stuck long after he laid down his right to bear arms. I think at one point he even joined the NRA, adorning his garage with one of its stickers, despite remaining fiercely liberal.

He’s been a medicine man for as long as I can remember. Room full of homeopathic tools and remedies. Dedicated to self improvement and reflection. He is the person who first taught me about remaining in the present moment. A few years ago a cousin and I laughed about being on his email list of new age spam. Blasting off weekly articles about the vagus nerve, benefits of meditation, deep breathing, and other mental health solutions. I’d laugh at these emails and barely read them. Now, I find myself searching for and needing them more than ever.

One of his dreams before he died was to go sailing for the first time, but logistically we never swung it. He did however come and see my boat when I was on the Hudson River. He came aboard and pretended to talk into the VHF radio, he called my boat utilitarian with a nod of approval, and said he couldn’t wait to shit in my bucket one day.

On my twenty-eighth birthday he left me a voicemail misusing sailing terms. Saying he hoped I was tuning my sails, and enjoying the perfect cut of my jib. I wish I still had that voicemail.

My first tattoo was in honor of him. He had a snake on his forearm. Faded and torn from the 1950s. I wanted the same, only the stick figure version, as a testament to his unfading greatness.

Every time I visited I wanted something to take with me that was his. A CD, a hat, a pair of socks, his old bicycle, his old tent. He’d always say, “You’re not getting another thing out of me this time! You’d take the shirt off my back.” And it’s true, I would. But he always gave in, shaking his head and handing over his possessions.

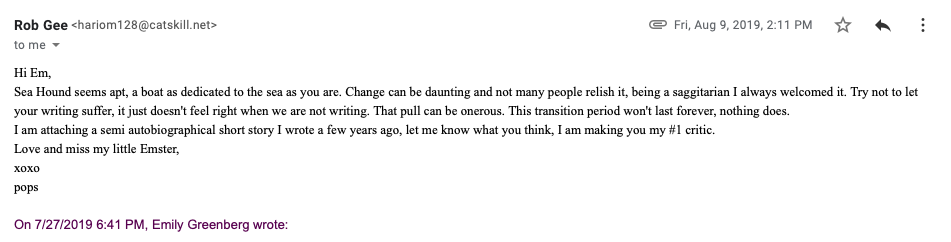

He is a published writer, fantastic storyteller, and giver of the most sage advice. He is a guru, a chief, and a rock to many. He used to tell me that he always reads my writing, and even if he doesn’t comment to just know that he is always there, reading it.

When I was working as a waitress saving tips to buy my first boat I waited on an eccentric man who turned out to be clairvoyant. As I began to walk away from his table he grabbed my arm and asked me in a dead serious tone, “do the names Cynthia and Robert mean anything to you?”

“Why, yes,” I said rather confused. “Cynthia is my aunt and Robert is my grandfather. They are two of the dearest people to me. My grandfather is my favorite person. ”

“Ah,” he said rather satisfactorily. “They’re with you always.”

I’ve always held on to that sentiment

As time goes on, the older I get, the darker the world seems to become. Climate change. Injustice. Someone dies. Another breakup. More lights go out. My grandfather has always helped remind me of who I really am. Beneath anxiety is a true essence he could always extract.

“You’ll do anything for a laugh,” he’d say, reminding me of my sense of humor.

But soon I won’t have that on the physical plane. I can’t just show up on my grandparents doorstep anymore when I need some no strings attached, unconditional support. It’s time to grow up. I’ll have to turn inward to access the infinite source of my grandfathers love and wisdom because soon, that’s the only place where it will exist.

When I’m feeling low and I wish I could just have some of what he’s got I’ll have to remember that I do.

That he is, quite literally, with me always.

That he was a great man, and I had the great privilege to feel like his favorite.

I am incredibly honored and excited to announce that I’ve been featured in SAIL Magazine and its latest article Sailor-Punk and the State of Cruising. I’m beyond stoked! Not only am I featured next to the legendary Moxie Marlinspike and the kids from Hold Fast but the editor named me his personal favorite young sailor blogger. I’m also really excited to be referred to as a sailor punk. It’s an identity I embrace, but I was never really in the punk scene on land, or on the water. So even though in my heart I felt like a boat punk, I wasn’t sure I qualified. In light of this recent honorable mention I figured I might get some new readers, and a brief update was in order.

I’m currently working as a deck hand and living aboard a 100-foot schooner on the Chesapeake Bay. After launching my boat in March the budget was busted. My money for the Bahamas was non-existent and to be honest, the state of affairs onboard Vanu, despite so many months in the yard, were still precarious. On top of this I had to borrow nearly $700 from my dad to bail my ass out of Belize after the boat delivery from hell. I did eventually wind up getting that $700 back from the captain by threatening him with a lien on his boat, but that’s another story.

I journeyed my little boat from Florida back up to the Chesapeake Bay on a five-week voyage of sorts to start my new job. The trip was filled with a constantly failing electrical system, getting chased by wild horses, gales, coming face to face with my past traumas, great days sailing, bad days motoring, time offshore, time inshore. There were times I wanted to run my boat up on a sand bar and walk off forever with nothing but a backpack, and there were times I didn’t want it to end. Oh yeah, I also fell in love with an engineless circumnavigator who designs and builds autopilots and sells them.

I learned what this boat was truly capable of for the first time. I cried. It made me fucking cry to feel that. I finally learned how to make passages. Which is why, as of now, I am continuing to sail and work on the structural refit of my boat, until the next boat presents itself. I have to take what I learned on this trip and apply it. I have to keep going. There will be another boat in the near future but until then I just have to make money. Save it. Keep working on Vanu and practicing sailing her. I’ve got a big wide river and lots of little creeks that I’ve already begun to sail and explore.

I want to tell you all more about this, but please be patient with me. I am working 12-hours a day on the tall ship, and when I’m not doing that I’m usually frantically trying to keep my boat safe. She is currently tied to a broken dock off of a fisherman’s museum with yet another leak below the water line. This time it’s the fiberglass tube that houses the rudder shaft. It’s a slow leak, but it needs to be remedied. I plan to make this repair by careening the boat and patching it from the inside.

I just spent the last two hours of my day off cleaning my electrical connections. The rest of the day was spent inside the belly of my boat pin pointing the leak. So, my apologies for the lack of blog posts, but I can assure you that if you hold fast you won’t be disappointed with the content to come. Standing by channel 1-6.

What happens when you fall in love too fast, or you just think you’re in love, or you’re in love with the idea of someone? For me, taking things slow is a near impossibility. My boat moves slow while my heart beats fast. I’m always just coming or going. Running aground hard and then floating off with the tide. Luffing loudly in irons and then silently sailing away. Time is sped up when you’re traveling around on a little boat. Strangers become friends. Friends become lovers. Lovers become strangers. A new port becomes home and then you leave it all behind. I call it boat years. Like dog years.

It seemed like we had met long before we had met. I was the only young, live aboard sailor on Lake Champlain, but there had been one before me.

“Too bad you weren’t here a few years ago, there was a sailor boy just like you.” “You remind us of this sailor boy that was here. He left. You would have liked him.”

One night my dearest friend on the lake regaled me of stories of this seeming kindred spirit sailor. The stories he told were meant to warn me, but they just made me like him more.

“He went south on someone else’s boat. He was always sailing on and off the dock. Never using his engine. When he left he got in an accident and lost the use of his right arm. He learned to sail again with one hand. Got another boat and headed south again. There’s all these stories now of him sailing engineless through bridges along the ICW. He has excellent boat handling skills, but he’s reckless.”

Engineless? Through bridges? One working arm? I was intrigued.

I made a film about sailing in an effort to raise money for my trip south and the sailor boy saw it. He messaged me. Then we emailed. Then we talked on the phone.

“You remind me of me,” he said.

He was helping as crew on an Alberg 30 headed south at the same time as me from a different lake. We just kept missing each other. He was always a few days or weeks ahead of me. We tried to meet on the canasl, on the Hudson, in New Jersey. By the time they reached the Chesapeake it was too late. I was too far north and they were quickly moving south. We’d have to try again some other time.

Eventually I ran out of money. I had tried to recoup some of it in a city further north, but still had everything to do to get my boat actually seaworthy. I was tired of the intracoastal waterway. I wanted to go to sea, but everyday I meandered down the straight waterway in search of a place to rebuild my bank account and my boat so that could actually happen.

Then we met in person for the first time in West Palm Beach and it felt like I had met my soul mate. We were both Gemini. We weighed the same amount. We both had eaten too much salt on our journeys down the coast, alone, which caused our poop to turn the color of sand (and both, subsequently, googled it and feared we were having liver failure). He was my lost twin. He was going to be my third hand, I was going to be his right hand. Who else could have gotten into the same taupe poop sailing scenario? It was clearly meant to be.

I had a feeling like I was falling too fast down a flight of stairs. I knew that I should tread lightly. I was not where I wanted to be with my boat, and therefore myself, and it wasn’t the right time to be entertaining romantic entanglements. Especially with a person equal in intensity to me. But I also knew I was going to do it anyway.

I looked at him and said, “you remind me of a mistake I made in high school,” and we decided to sail together down to the keys.

We anchored in front of the lighthouse and jetty of Hillsboro inlet and flew a kite. I washed his hair. He made a gourmet meal out of my humble provisions. We slept in separate port and starboard settee’s, whispering into the wee hours about sailing around the world. When the wind picked up that night and the swells became uncomfortable I just pretended I was at sea. In the Bay of Biscayne we reached along in 25 knots under double reefed main and working jib. The sail combination was perfect. There was saltwater all over the cabin floor which had come through the hawse pipe, I’d deduced. But I was prepared if it had come from below the waterline. I didn’t panic. While he sailed my boat and I tended to her elsewhere I remember thinking, “I could go to sea with this person.”

Or was it, “could I go to sea with this person?”

But despite all this, I knew it wasn’t right. I reminded myself to tread lightly. I was still broken. My boat was still broken. My friend and his boat were also, essentially, broken.

So I tried to break it off in key largo. We were both broke, underfed (obviously we had too much salt in our diets), and needed to get our shit together before we could actually ever be together. But instead we decided we’d try to get our shit together while being together.

We stayed in the keys a while, and then headed back to West Palm Beach where his boat was, and where shit started to break down. There were positive things that happened there and while we were together; like the stepping of my mast and new standing rigging, a few friendships that were my saving grace, finding a little bit of work, getting offered a free boat and selling it—but mostly it was the wrong situation for me and my boat.

In the worst of times he was manic, I was depressed. He drank, I didn’t. He wanted a big boat, I wanted to rebuild my small one. He was reckless, I was cautious. He wanted to be a captain, and so did I. It became explosive. I threw a plate. He screamed at me about bottom paint. We could not be on the same boat.

He got an offer to crew on some blue water, and I limped out of town having learned a lesson. Sometimes having the most seemingly uncommon things in common, isn’t enough. Sometimes even taupe poop isn’t enough. We were the two most incompatible people on a tiny boat together. We were still the two most incompatible people between two tiny boats. Even on land, we learned later after trying to do long distance, we remained the two most incompatible people.

We had been surrounded by water, but were fire and gasoline.

The boathouse and my time here feels like a blur. Visiting sailors have always been welcome here. It’s how I first ended up here, and I’ve kept the tradition alive. Two schooner boys are our next guests. I remember the first one that showed up. Scott from SV Steady Drifter. His experiences in the Bahamas had rendered him changed. Then there was Johnny and Pete, who I would sail my boat with for the final time before hauling her. Chris and his Nor’sea which laid at the dock because work kept him chained to a ship that wasn’t his own.

They’re all land based now, too.

Never trust sailors on land. There’s more at stake out there, so there’s no time for trivial things. Like the anxieties of modern life and modern relationships. Being out there makes me a better person. Being out there makes me more independent and sharpens my desicion making skills. Out there everything is simple, even though the reality and rules are harsh.

On land everything gets misconstrued, so I had to start keeping a planner.

“I don’t do well alone,” my friend says. This is over the phone. Maybe that’s why he’s talking to me at 1 a.m. The funny thing about being alone is I only notice it when someone else comes along and points it out. Going down the Hudson river, getting shit out into the Atlantic ocean at the bottom of the tidal universe, my six horse power engine buzzing and my main sail struggling to stay full of air in the busy harbor. The passing ferry wakes are mountains I climb and careen down. There are tankers, container ships, water taxis and I don’t know which way to go to get out of their way, so I just hug the buoys. Content with running aground or into a bridge pillar if it means avoiding collision with one of them. I’m shit out into the Atlantic ocean and the wind fills my sail. I turn off the engine.

I am completely alone.

Everywhere I go there seems to be some old salt with thousands of miles under their keel that believes in me. However for every one of them, there is someone who thinks I am fool hearted. -From the Log, May 2017

I arrived in Northern Florida after meandering my way along the East Coast waterways from Lake Champlain. I was broke and looking for work so I could fix my boat and venture beyond the protected waters of the Intracoastal, but it was still far too cold even that far south. I made a little bit of money and had two choices: I had enough to stay there one more month if I kept chasing job leads or I could keep going and chase leads at the next place, which happened to be the Keys! It was warmer in the keys. The few nights before that had been below freezing. I figured if I was going to be broke and looking for work I might as well be warm.

I readied the boat for passages south! Albeit intracoastal passages, they were passages nonetheless on this voyage of sorts! My newly constructed dinghy was launched, I had replaced my parting topping lift, wired an LED light for the galley, and was closely monitoring my through hull leaks. In the unlikely event of some through hull failure I had bungs at the ready and was going to be in the keys where it’s so shallow you can easily run aground before the boat would ever sink. With my sketchy standing rigging still no worse for ware I was essentially ready to go anywhere on the inside!

I wasn’t sure what this journey would bring, but I figured closer to a place where I could work on my boat so she was fit for the ocean! For more adventure! For… the sea! Instead my eyes were opened to what was right in front of me. An adventure in its own right!

“So I’m trying to get my boat on the hard.”

I’m talking to Logan. He’s in Puerto Rico having sailed there from Lake Worth a couple of months ago. We met in Cocoa Beach, FL, and lamented the Florida ICW together until he left to cross the Gulf Stream and I continued along the ditch in hopes of finding work and getting my boat fit for sea.

“One of the projects is closing up my through hulls. Doing it the right way means removing the through hull fittings, grinding a five inch bevel and filling it with layers of glass. And I’m like, can’t I just put some wooden bungs in there with 5200, close my leaky through hull fittings and call it good?”

“Absolutely!” he said. “You can even use a potato. Carrots work too.”

I’m laughing but know he’s serious. This is coming from the dude who when we first met asked me within minutes, “Have you been dismasted… yet?” One day while looking for his through hulls I found a corroded seacock handle that looked about ready to snap off. This was days before his intended blue water passages. When I pointed it out he simply shrugged. He had plenty of potatoes and carrots onboard, so I assume he wasn’t worried.

Despite his antics Logan was quite the competent captain. His boat, the Good Ship Dolphin, was loosely based on a Columbia 28, however she was much more cavernous and carried an expansive amount of tools, fermented foods, and other supplies intended for delivery to hurricane stricken islands.

Dolphin was a fiberglass Columbia 26. Logan acquired the boat from the previous owner, Rebecca Rankin. She and Dolphin had many adventures together.

Rebecca and her previous partner had done their best to make the rig bullet proof after a dismasting during a storm in the Florida Keys. She wound up making a mast step out of laminated plywood that extended seven inches up the mast, and spreaders made from white oak and stainless steel, “so Dolphin would never lose her mast again,” Logan said. The standing rigging itself was redone sailor gypsy style with nicro press fittings and a hand swaging tool. Because the backstay was too short, a shackle and some links of a chain were used for proper tension.

(At the time I was embarking down my own rabbit hole of redoing my standing rigging and had a breakthrough seeing how it was done on the Good Ship. The only reason I would wind up not going that route was because I got a crazy deal on machine swaged fittings…but I digress).

The boat was, essentially, very seaworthy as long as there was a potato at hand in case of a failing through hull. There was also mention of a rotten skeg, but what were a thousand nautical miles with a rotten skeg to boat like Dolphin?

Nothing of much concern, apparently, because Dolphin made it all the way to Puerto Rico no worse for ware complete with waterspouts, close whale encounters, and a detention in the Dominican Republic where his crew abandoned ship. Logan wound up single handing the rest of the way to Peurto Rico.

“I hope you are nearing the sea my friend,” Logan wrote to me ten days after he’d arrived and had begun carpentry hurricane relief efforts on the island. “Many mysteries.”

An old woman passes by the waterfront on her bicycle. Colorful clothing, a heart flag hanging from her seat, a basket. Her aging terrier trots in tow, faithfully, ten feet behind her.

“Is that going to be me when I’m old?” I ask Scott.

He left his boat near Miami to return north by car, to square away business, before crossing the Gulf Stream. He has come to see me en route.

“I don’t see it,” he says.

“Well, then what do you see?”

He looks at me for a moment, and then out at the harbor. My boat is moored there quietly, next to the dilapidated pier. Patiently waiting for me to make a decision on what we will do next.

“I see you in an old boat. Inviting kids onboard and telling sea stories in a raspy voice. Feeding them sardines,” he says.

“Yeah!” I say. Getting into the vision now. “And I’m permanently hunched over from years spent on boats, sitting next to an oil lamp.”

“Right, and the boat is one of those boat’s that is completely set up but isn’t going anywhere. And everyone knows it’s not going anywhere.”

“It’s not going anywhere because it’s already been everywhere.”

“Exactly,” he says. “You both are retired. You and your boat.”

“Wow,” I say smiling to myself and wondering aloud. “I hope I’m on my way towards that.”

Soon the clouds ascend and I rush out of the car to row back to the boat and miss the rain. I leave a small pile of beach treasures in his car. The pointed claw of a horseshoe crab, a piece of coral, a tiny coconut husk. My oars cut through the water. I use my entire body to fight the current. My shoulders, elbows, chest. My feet brace the aft seat. The sound of oars in water, although so familiar at this point, always manage to instill in me a great sense of adventure.

Cities on the water way are so strange. Step away from the harbor front streets, the marinas, the anchorages and it’s as if you’re not even near the water at all anymore. Suddenly it’s suburban sprawl and traffic and you find yourself riding a borrowed mountain bike down a highway sidewalk, diverting into a neighborhood that resembles the hood, just trying to escape the lights, and noise, and rain— in order to get back to your boat.

One mile inland and, it seems, people have no fucking idea they are anywhere near the sea.

Humans are kind to me. For whatever reason I find myself constantly surrounded by people and forming unlikely friendships. Sometimes I forget how to be alone. Sometimes I’m afraid it will end—the people I already know, the people I haven’t met yet. Not only will they not be here physically, they won’t be anywhere. They won’t be in any pocket of my heart, the land or the waterway.

Technology baffles me. So many people keep up with me, meet up with me, and ultimately alter my life in positive ways that put me one step closer to my goal—which is, in a sense, to be away from them completely. To be alone on the sea.

There is not one moment of one day where I don’t think about this boat, my means and my character—and how all that equates to the possibility of actually achieving what it is I envision.

“You are in charge of what happens next,” Chris said to me as I left her dock and historic estate. We were discussing the possibility of my return to that small Chesapeake town for what would be an overhaul to the boat. Another step, in a series of steps and seasons, to be out there on the sea safely, sustainably, solo.

“What’s new in your love life?” my oldest friend asked me in a text message.

“Not much,” I replied. “Just in a solid, committed relationship with my boat.”

My conversations with those furthest away who know me best are reduced to screens. My face-to-face conversations happen with people I hardly know and may never see again. These conversations all feel equally important.

“The intercoastal is that way,” a sailor I traveled with told me twice.

Once when we were at the dock discussing the next day’s route and another time when we were underway. The natural direction I thought to go in both those instances led to the open ocean… not the protected waterway.

When we parted ways and I pulled into port to wait for important mail, he continued on into the next canal and body of water where he hoped to wait for a good weather window and sail offshore.

His mast now far from sight I called out on the radio anyway.

“Good luck out there on the lonely blue highway,” I said, essentially, to no one.