LISTEN HERE!!!!! https://www.marketplace.org/2023/07/13/yacht-broker-turned-her-love-of-sailing-into-a-career-where-theres-only-room-for-growth/

Support SAILING SHORTS on Patreon! Experimental short films chronicling east coast sailors and adventures!

First up meet Anna & George Jordan- a cape cod fishing family that salvaged and restored a 76-foot steel schooner.

Next is Eddie & Dean. Teen brothers who refit a boat with the help of their parents to “sail the world” in lieu of college.

If you enjoyed these videos please join the SAILING SHORTS patreon for only $5 a month @ www.patreon.com/ADHDSAILOR

Many exciting thing abound like the dark side of sailing culture, yacht broker wars, a new brand and website launch, and a portfolio update so anyone can catch up on my latest sailing articles from SAIL magazine and more.

The dynamic duo is back again. That’s right, I am repping for Melanie Neale at Sunshine Cruising Yachts from now until forever. Hit me up at emily@suncruising.com for your yacht broker needs. Coastal North Carolina & Long Island, NY are my current areas.

Massive portfolio update is here: YACHTING JOURNALIST

articles from towndock, spin sheet, prop talk, SAIL mag

And last but not least, coming soon…

You can donate to the BOAT GIRLS FUND here

Courtesy of Towndock.net, 1963 sailing vessel Teal arrives in the harbor for some much needed refinishing.

Genoa, tri-radial by Evolution Sails / Latell & Ailsworth Sailmakers, HQ, Sailloft & Repair, Deltaville, VA ! Made in the USA

Mainsail Track, Tidesmarine, Hi-density extruded teflon, low-friction mainsail system 2021

Vintage Hydrovane, Self-steering wind vane; British Columbia. Furlex roller furling

Boat hull/design; Tripp 29; Tripp-Lentsch, built by Amsterdam Shipyard in the Netherlands, 1963

Like and follow on Instagram @ Dinghydreams and YouTube @dinghydreams

Take a look inside the magic that happens when community, career, passion, and a conscious approach to capitalism collide! Meet the literal sailmakers of Latell Ailsworth Sails, a trade that employs both traditional sailing skills and the latest yachting industry technology. In a marine industry moving more and more toward globalization and remote consulting–Latell Ailsworth is a brand and business that prides itself on it’s partnership overseas, as well as a strong local and regional East Coast presence. Is it any wonder Latell Ailsworth Sails, of Deltaville, VA–a small yachting center on the southern Chesapeake Bay–is a division of a Kiwi Company?

The kiwi’s may be a small island country but has a strong yachting history, along with modern democratic socialist practices. It’s capital, Auckland–is known as the City of Sails. In fact, its the first place I ever sailed and where I got into this whole sailing mess to begin with! My first day sail ever was in NZ (fun fact: the letter “Z” is pronounced “Zed” in N Zed). Latell Ailsworth overseas partner is Evolution Sails, a New Zealand sailmaking parent company.

I loved New Zealand and have pretty much just been trying to get back there ever since. By yacht of course. I told Latell I’d get the Evolution logo tattooed on me (which he did not endorse…yet) as a testament to my commitment endorsing this opportunity to low key partner Evolution Sails–I mean maybe the parent company wants to sponsor my return to Aoteaora (New Zealand in Maouri, literally translated to Land of the Long White Cloud).

Now I’m day dreaming again.

Sometimes it feels like I have a goal, I chase it, I get the opportunity, and then I have to do the actual work and the entire time I’m just dreaming of the next thing to chase. So before I get back to New Zealand I’ve got to just get back to my boat eight hours east of my current locale, and well, go finish my new Genoa furling headsail a few hours south of my boat, and then bring it to my boat, bend it on, photograph it and send it in on time for the deadline to SAIL Magazine to meet my contract for the October 2022 Issue and the Annapolis International Sailboat show.

Ha, and then sail my boat down of course. To where I have to finish refitting her and launch some entrepreneurial endeavors.

Can I pull it off? I usually do, in some way or another. It always works out in the end.

If you enjoy this video please check out @dinghydreams on YOUTUBE + Instagram! Help keep this site afloat please consider a donation.

ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK! Preview! Full video coming soon! A preview of sailing vlog featuring a run-in with NYPD helicopters while sailing engineless through New York City in December. Stay tuned for the full video!

Once again in collaboration with YouTube’r and single-hander Sam Holmes, we test a survival suit and it turns out surprisingly whimsical! From his channel “Sam Holmes Sailing.”

Please like, share & subscribe! Patreon coming soon!

SUPPORT THE ARTS! Thank you for your interest in maritime literature and other multimedia ventures on the high and low seas!

Where do you find the heart of sailing? Is it witnessing both a sunset and a sunrise at sea? Is it in a boatyard with no fresh water, skin itchy with fiberglass? Is it in stepping ashore after a long passage, and drinking sparkling water with a lemon you foraged next to an abandoned dock? Is it in being wet, cold, and slightly frightened?

Or Is it found somewhere else? Is it found in yacht clubs and private marinas? Is it found in a fully enclosed cockpits with electric winches? Or in that moment you cash in your stocks and buy a boat to sail off into the promised sunset, cocktail in hand?

In the harbor right now there are three boats, including myself, that are all “basically engineless.” Meaning we all have some kind of auxiliary propulsion that only really work under totally calm wind, wave, and current conditions. Whether it be an extremely underpowered 2.3 HP outboard, or an outboard with a shaft that isn’t long enough, or a dinghy hip tied. That means in any and almost all conditions we are sailing, unless it’s for some short stretches of the ICW.

Is it because we are broke? Young? Idealists? Perhaps a combination of all three.

I’ve been a vagabond since I was 22 and bought my first boat at 26. I’m 31 now. I haven’t paid rent, except for the odd slip at a marina here and there for a few months at a time, in ten years, and have held various jobs. I happened upon sailing by chance on a yacht delivery in New Zealand and sailed across a literal sea a thousand miles over ten days, and I’ve just been trying to get back to that ever since, on my own boat.

But I never felt stuck in life, in a career, or in the throngs of capitalism that so many people feel that leads them to quitting their jobs and searching for boats. I’ve felt stuck with no money and very unseaworthy boats, but I didn’t do what most of my generation did; which is basically get real jobs. And now that they’re in their thirties and sick of the grind they’re like, let’s get a boat.

And they go buy some plastic boat from the eighties with a comfortable interior and no inherent seaworthiness in its design, but it’s safe enough. They focus on having a good engine, and then motor across the Gulf Stream to the Bahamas. They follow the “Thornless Path” and motor sail in the calms that can be found in between the prevailing opposing winds. Until they eventually reach the Caribbean and it’s all downwind from there. They have enough money, and enough confidence, even never having never sailed before, that they make it just fine.

Lots of people do this, especially with the advent of YouTube. People are like, “Yo, I can live on a boat and make a YouTube channel to pay for it?!”

But I can tell you this is not where you will find the heart of sailing. That is something you really have to look for. This is where you will find a departure from it. I’ve been trying to find it for years by now of living aboard and messing around with boats, and I still know nothing. “Remember you know nothing,” an old schooner captain told me. That’s what makes you a good sailor, he said. A good captain.

Famous sailor Nancy Griffith said, “know the limitations of your crew and your boat.” Crew, for the most part, has usually been only me. And I’ve scrutinized both myself and my boats heavily when weighing certain passages. I worked at marinas as a way into even learning about boats. My first boat I stuck to lake Champlain, my second I took down the Hudson River and to the Florida keys, only spending a little time offshore. The boat simply wasn’t prepared for passage making. Most of the offshore sailing I’d done before my current boat, was on boat deliveries. So I hold myself to that standard of seaworthiness, of what I’ve seen on the sea.

I spend more time fixing my shit to be at sea then I do actually at sea. I have to fix boats so often because I don’t have money, so I’m pretty DIY. The trouble is I really don’t trust my work. I rely on people with much more skill than I have to tell me if I’ve done something right. For me, the goal is to make my boat as safe and comfortable as possible on the sea. It’s been and continue to be arduous, refitting old boats to be sustainable in such an inhospitable environment, with little money and no formal training.

Sometimes I envy the other kinds of travelers. The backpackers. The ones who hoof it, bus it, ride planes and hop trains. But that’s not for me. Devoted to the sea. And if I can’t be there, damn it, I’ll be on land just trying to get there… because nothing else matters.

[email-subscribers-form id=”1″]

COMRADES,

On Labor Day weekend 2020 I hauled my boat for three days and three days only to paint the bottom, remove the old prop shaft and fiberglass the hole, and make a small repair to the rudder that will prevent me from losing the rudder in the event of fastener failure.

It was a community event. The only reason it managed to happen at all was because I was getting a deal on the fees due to the long weekend and no yachts scheduled for the space.

Sailors and friends came and went. The boatyard manager (and part owner of the yard and marina) offered advice and answered questions. The shipwright (also co-owner) even helped to remove the shaft. The shipwright, my friend and fellow she-pirate, and I all pushed the prop at the same time to finally break it. Then our ‘helper’ grabbed the sawzall and cut into my boat!

“Ack!” I shrieked. “I didn’t consent! You cant charge me for that!”

He laughed and assured me he wasn’t going to. Offered some words of encouragement to keep chasing the dream at sea. Everyone was in high spirits and it was a true collectivist effort. That night I even got a stick-n-poke tattoo onboard my boat, in the yard, commemorating the experience.

But there was a third owner of the marina and boatyard, who didn’t like the cheerful and chummy nature between me and his partners.

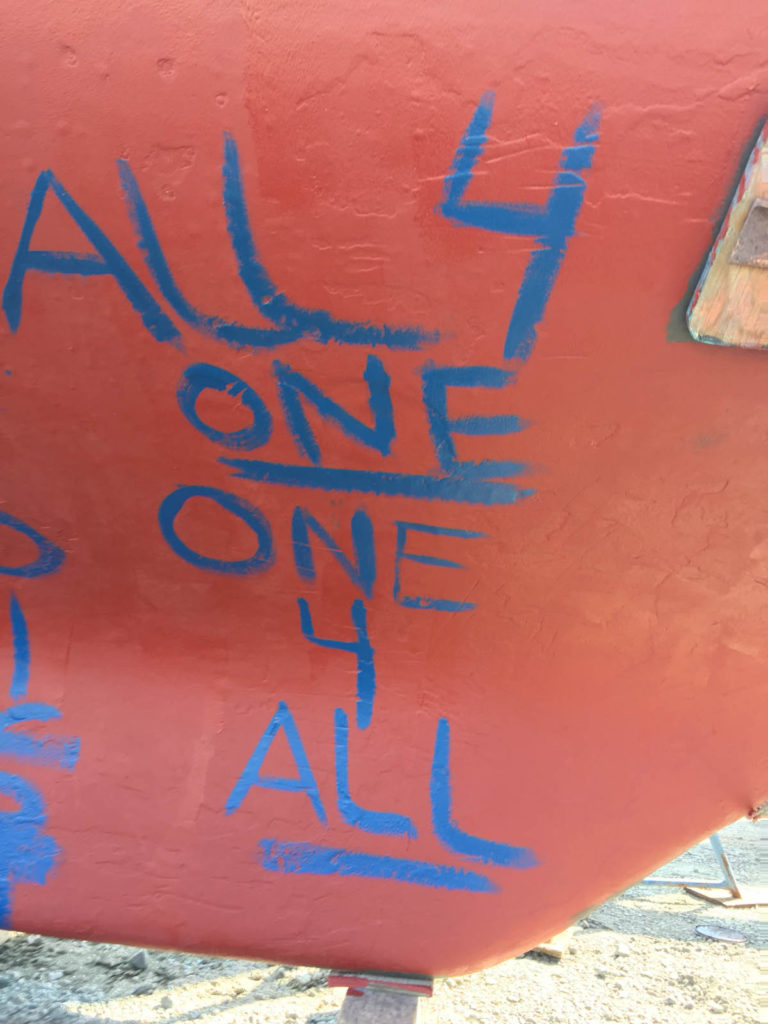

By day three I’d salvaged three partial cans of bottom paint all different colors and set to work anti fouling. It was then I was struck by my brilliant idea to add some peaceful, anarcho, collectivist, anti-racist messages to the bottom.

Solidarity, Comrades; Love is free; the acronym for Black Lives Matter; Resist; The Climate Crisis is Real; No Justice No Peace; and even the infamous line from the back of the Dr. Bronner’s soap bottle All for One, One for All; graced my keel.

I launched the next day, and was informed that the partner with the most share in the business was not going to honor the deal because the messages I had displayed. If I chose not to pay, the partner who did me the favor would be held responsible. So I did the right thing to not hurt someone who had tried to help me.

My friend and fellow-she pirate who helped me with my boat, who is also the sole care taker of a salty old boat and four children after her husband passed away during their years cruising together on a traditional gaff-rigged 29 footer, was also penalized and her deal for boat storage was also no longer going to be acknowledged.

I’m asking for donations to recoup the funds from the deal that was not honored. That amounts to $155. Anything extra will be given to my friend for her unanticipated fees upwards of $500. If we somehow raise all of that any remaining donations will be redistributed to mutual aid funds for folks affected by the wildfires on the west coast.

Thank you for your support.

Solidarity, comrades.

A surveyor wouldn’t touch it with a ten foot pole (I know this because my friend’s a surveyor and said so), but that’s a legit home made 12-volt lithium battery for $300 vs. the $700-1000 you’ll pay for a “marine” one.

Each cell is about three volts and that little red box is a battery management system (BMS), which keeps it all distributed evenly. The wires off the BMS are soldered to the positive end of each cell . There’s even a fuse on the battery to limit risk of fire in case the battery shorts out. Plus, it’s lithium ion vs. lithium iron. Lithium iron is apparently the more dangerous one, and if one cell melts or gets too hot it can start to burn any cell that is next to it.

It’s the way of the future, and lithium 12-volt batteries are way more efficient and longer lasting than lead acid. But of course like anything it comes with risks and consequences.

Where did the lithium in my batteries come from? Probably some horrible mining practice. I’ll look into that. It seems we just can’t escape the environmental impacts that come with being a human and consumer.

In the meantime I’ll be getting lots of work done on my computer because I can finally plug it in on board. This is the first time ever I’m able to have sufficient power on a boat I’ve owned. I even have a food processor. Hummus anyone? Plenty of solar aboard to charge everything and this battery can easily be disconnected and brought to land to charge! They’re also so much lighter than lead acid, and if you’re really clever you can swap them back and forth with your electric bicycle which is all these cells are anyway. Electric bike batteries.

I am not that type of clever, however, so just leave me to some basic carpentry and fiberglassing. This addition to Sohund is definitely not my creation, but I’ll take it!

Hang in there folks. Spring is almost here. I came out of the boat and I didn’t see my shadow, so– I’m sure of it.

A short note: Please sign up for email updates below! My subscribers all got deleted! All that’s left are 13 randoms and one of them has already sent me hate mail saying I am deranged and to take him off the mailing list. Sorry, but I don’t even know how you got ON the mailing list let alone how to get off it . So I guess he’s out of luck.[email-subscribers-form id="1"]

Happy New Year, dear readers!

Many boat and writing projects abound, but I’m stuck in a windy anchorage on a hurricane devastated island.

A fellow engineless sailor is here who helped us get access to bikes, free laundry in a FEMA trailer, and some apples. He lost me, though, when he said he questioned the existence of sexism and asked if feminism was the same as chauvinism. He then seemed surprised when I answered no. And, in his grandest gesture of misogyny he said, “I need to get me one of those,” in reference to a girlfriend who would clean his boat for him. It’s sad because he’s the only other boat around these parts without an engine and he came off so helpful, but it’s 2020 not 1920.

I had no choice but to kick him off my boat even though he’d just shared a couple pounds of fresh shrimp with us.

Should be some wind to sail on out of here soon enough!

I want to express my gratitude for those of you that still read this damn thing and for those who are just starting to. I hope you all get a little further along in your journeys.

Don’t forget submissions are open for Heartwreck: Romantic Disasters at Sea, a collection of stories about love and loss on boats.

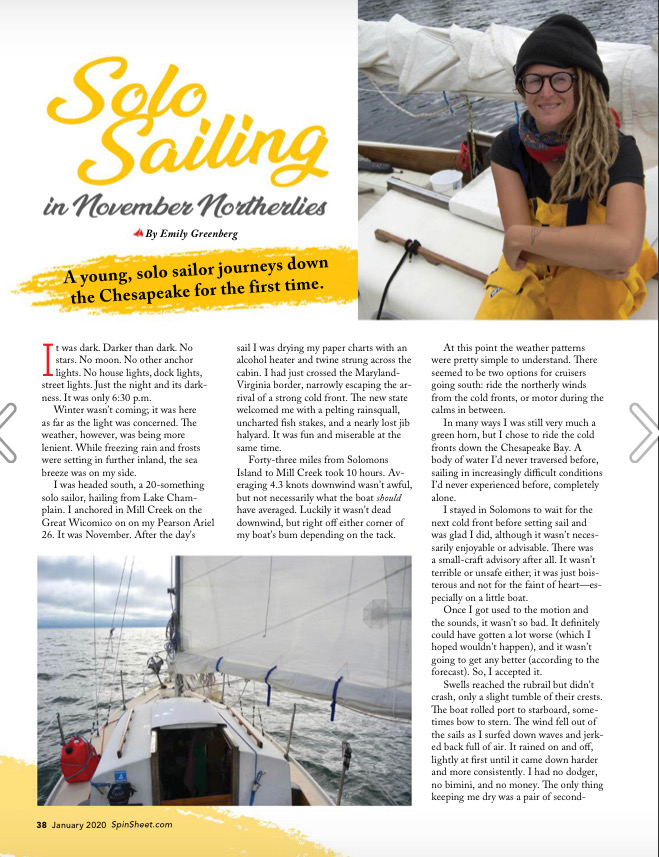

Also, check out my article published in SpinSheet Magazine about riding cold fronts down the Chesapeake Bay.

I finally got my writing portfolio moved over here, so check it out and contact me for any of your writing or editing needs.

I’ll get this damn boat seaworthy again soon enough, in the meantime I’ll be here offending all the white men who are holding on to the very last of their undeserved privilege!

Here’s to surviving late stage capitalism, the climate crisis, and all the inevitable break ups and deaths this year!

See you out there!

I just finished the worst bottom job I’ve ever done—because I don’t have the money or the time to scrape, grind, or sand blast off every last colossal, continent sized patch of old, thick antifouling paint down to bare fiberglass to make way for a proper barrier coat. There’s the right way, and then there’s the right now way. The bottom, I feel, is going to be an uphill battle because of this.

Fiber glassing in two through hulls turned into six because of a previous owners dodgy work. My personal favorite are the two holes (below the water line) that he chose to close up using nothing but a mixture of epoxy resin and sealant. Like most of his efforts on this boat, good intentioned but poorly executed. Such as the cockpit drain through hull that was installed with a bevel so large, the hull itself was ground down to where it was actually compromised structurally. I also must mention the defunct depth sounder right at the stem of the boat that was protected from popping out by a fiberglassed piece of wood on the inside of the hull, which I cracked within my first week of owning this vessel. Build it all back up has been the theme.

The mast has been stripped bare. All tangs replaced. Halyards rearranged and the standing rigging waits for its final bends…but first install the seacocks. Then launch. Being on anchor with no mast while we finish the rigging on land might suck, but not nearly as bad as being in a toxic boatyard for another day.

I used to want to earn respect at boatyards; now I just want to get out of them. When all this is said and done I’ll have a mere $180 left to my hand, but I beg anyone to name one great sailing adventure that wasn’t grossly underfunded.

If you enjoy this blog please consider a donation so I can share more stories with you!

March 13, 2019

At some point you just have to say fuck it, and go sailing. I know this boat. I know all its weaknesses. I know what it can take. I also know what I can take, which is probably a lot less. I know how quickly it can change out there. That’s why some passages are…questionable. On a good day this boat can do it out there. On a good day any boat can do it out there. This is not the boat I want to be in when shit hits the fan. At least not in its present condition.

I think at this point being on the water is intrinsic to my being; or I’m jaded. I just find it hard to fully immerse myself in the moment and enjoy when I feel a lot of pressure to prove myself and make this boat respectable.

Let’s see I have six weeks, maybe eight, to finish the rest of the work to this boat. Did I mention I want to refinish the interior on this piece of shit? I know, I know, she’s my piece of shit which is precisely why I am making her pretty. Shit, I might AirBNB her when I get wherever the fuck it is I’m going (north).

And even though it pains me not to be in the Bahamas today was a win. Moving the boat to the other side of the waterway. The island side. I can hear the ocean over the dunes and mangroves. There’s a lighthouse. Some pretty boats. You can land your dinghy at the public launch ramp or hide it if you want to leave it for longer. They can ticket your dinghy, but I have a feeling Loner will slip through the cracks.

There are some dero* boats here (*side note: my Kiwi friend used to call me/Vanu “dero.” It is literally short for derelict but in Kiwi slang it’s used endearingly for someone that is hobo/hardcore/crusty or whatever. Someone usually broke, traveling, and kind of dirty. I’ve adopted the term to refer to the derelict boat problem in Florida). But I’m not worried about them. I can keep to myself, speak their language, or defend myself if ever necessary.

I’ve decided that after Vanu I’m going to own a boat a year until I find “the one.” Being on Vanu has literally been a time warp. Throw in daylight savings time and, well, I’m tired of the struggle. I’m selling out. I’m getting a job. And then I’m getting another boat.

In the meantime I’ll be illegally stashing my dinghy, prepping the boat, and doing odd jobs here and there before leaving this town, out the inlet and onto the next adventure. On a good day, of course.

It’s blowing. Out of the north. Late for the season. Although, I guess…not anymore. The northers, “never used to come all the way into March until this year,” I remember Bahamian Mike saying in West Palm Beach. That was last year. It’s March 18. Still too early to head north. This one, when it is said and done, will have blown for four days. Today’s the worst of it. It’s supposed to calm down. The gusts are definitely up to gale force and it’s a steady 25-30. This is exactly what NOAA has predicted, so, I’m not surprised.

I’m yacht sitting so I’ve left Vanu to fend for herself. Which of course begged the question, at least in my mind, if it was bad seamanship. She has two good anchors out, chafe gear, adequate scope, mud bottom. I did an online poll asking “Is it bad seamanship to leave your boat at anchor to fend for itself in a gale?” and mostly everyone voted it wasn’t. Not bad seamanship. I mean think about it. Most people who own boats aren’t with or on the boat when it’s blowing a gale. It’s at the dock, or on it’s mooring. Am I right? Unless they’re out cruising, or it’s the weekend, the boat is on the water and its owner is on land (or in my case on another boat).

Because most boats are at the dock more than they’re, “out there.” Am I right? Most of the boats at the very marina I’m sitting in right now don’t have people on them. Most of the boat’s at the mooring field my boat is anchored next to don’t either. That’s the only reason anyway cares about what I do and this blog anyway. People don’t pay attention because my boat and I are special, but because we’re out there doing it, (“which is more than most can say,” a friend has told me on more than one occasion when I’ve felt like a hack of a sailor).

A few people voted yes. That it is bad seamanship. But maybe they’ve just never been out there when it’s really bad. Bad enough to where you shouldn’t be out there. Or maybe they have. Maybe their entire lives are wrapped up in some boat that is simply irreplaceable, and they’d never think of leaving their boat to fend for itself when they could do a better job caring for it by being aboard. Or maybe they don’t know anything about boats at all. All I know is I’m glad I’m not on my little boat right now because I’d be all scared. I’d be checking the weather constantly to make sure it wouldn’t get worse, and probably be trying to identify strange noises, and bobbing around like a cork, and start wondering why I do this shit for fun, and eventually I’d get so tired that I’d be able to sleep with one ear open. I remember when I learned to sleep in a gale, and the many times I rode them out for several days because I couldn’t come to land during it. So I’m pretty grateful to not be on my boat right now.

What’s the worst case scenario anyway? She’d bounc off of things if she ever broke loose. That’s what pilings are for. I have liability insurance if she ends up damaging anyone’s property. I’ve got tow boat insurance if she ends up hard aground. The damage that would be caused to her would hopefully be nominal. She’s in a protected spot with mangroves and sand. She cannot be swept out to sea.

But even if it was a total loss…then what? I’d be sad but I’d be able to move on. I’d recover. Financially, emotionally. I certainly don’t want that to happen, and it’s highly unlikely, and I’ve done everything I could to prevent it other than being on the boat itself.

What would that mean anyway? Being on the boat? That I’m cold, miserable, unable to get any work done to the boat because she’s like a ghost ship heeling and walking up on her anchor and going beam to the wind every few gusts? Unable to get any work done on my computer because there’s not enough electricity or WIFI?

Here on the big boat at the marina I’ve filed my taxes, put all of my nautical miles together, made a sailing resume, written cover letters and applied to several boat jobs. I may have even landed one aboard a beautiful wooden cutter from 1935. I can almost already feel her journeys on the Pacific Ocean under my feet on her brightly varnished deck…but I digress.

The boat I’m yacht sitting is actually heeling now. Her lines are creaking. The cat is scared. She’s trying to tell me something. She exits through the open port light that functions as a cat door, but quickly comes back in traumatized. I pop my head out of the companionway. It’s still really blowing. The cat is meowing profusely. I go and get her littler box and bring it inside, since it’s too dangerous for her to go to the dock. She’s tiny and the gusts are big. Another gust comes and seems to radiate through the marina. It had to be 45 knots. I wonder how little Vanu is fairing. This is the last of it. It’s peaking, If she can just hold fast through tonight…

As we motored up the Rio Dulce and into the most majestic, lush, tranquil canyon that ever did exist the captain was stressed. We had to check out of the country and he didn’t know how much it would cost. He still hadn’t set up the foot pump for the water tank, and the gimbaled stove had also not been connected to the propane and tested yet. They both got done while I steered us out of the bay, but man were we cutting things close. While rowing back from customs we nearly got run over by a “launcha,” locally built wooden boats up to 25 feet long powered by sometimes massive outboard motors. This was a particularly large and fast launcha. I was watching it the entire time, but didn’t say anything to the Captain, waiting for him to look around at all but he was clearly in his own head.

“BOAT,” I yelled, right before it was almost too late. I stood up in the tippy rowboat ready to abandon it. The driver of the launcha saw my bright green shirt and my arms waving and veered off at the last minute from our bow. Within inches it seemed. It felt like a bad omen.

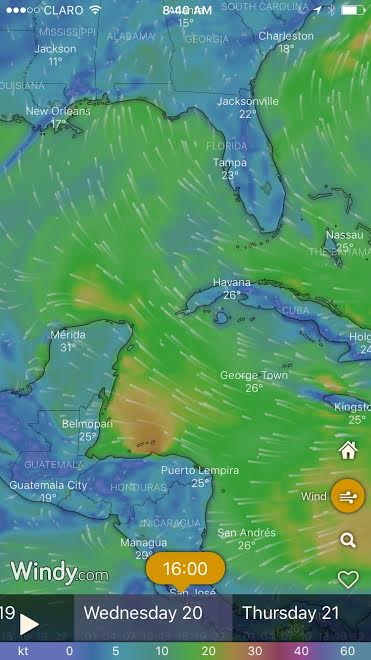

We motored out into the Gulf of Honduras and eventually met a brisk wind on the nose. According to the captain winds were predicted light and variable until a steady Southeast flow would ensue the next day. But even with steady trade winds the land has a funny effect on the winds outside of the Rio Dulce and it’s known to be a slog to get out of. That’s why the world cruising route favors the natural channel between the Guatemalan/Belizean coasts and the barrier reef. But we were not favoring the proven world cruising route, so we continued to claw our way offshore.

During our first night at sea in the Gulf of Honduras I counted 20 ships during my two watches. As we were tacking in between Guatemala and Honduras, my mind began to wander. These were some pretty impoverished nations. Pirate territory, maybe. Is that why so many cruisers favor the reef? The wind was dying and the captain came on deck for his watch. I voiced my concerns about pirates.

“Don’t mention that,” he said. As if I had jinxed us.

My nervous laughter returned. “Oh okay. Ha. Ha. Well, just might be a good idea to be have a plan.”

I went down below and am awoken an hour later to him calling

my name.

“GET UP HERE,” he says.

I poke my head out the companionway and it’s dead calm. The self-steering wind vane can’t do its job. We are motoring. He is readying his spear gun.

“What’s up?” I ask calmly.

“There was a boat.”

“What do you mean a boat?”

“A launcha, right behind us. It crossed our stern. It didn’t have any lights on. I shined the spot light on its hull and outboard motor.”

“Do you want me to get the flare gun?”

I come on deck although that seemed counter intuitive. If there were pirates isn’t it better they not see me on deck? There are no more signs of the boat. We sit there in silence. After a few minutes he now wants to talk about the plan for pirates. Give them anything they want I tell him. Of course, he says, you hide in the V-berth. He talks about how he could shoot them with the flare gun but the barrel that holds the flare is broken and he doesn’t know if it actually works. I sigh and go back down below. We don’t even have a working flare gun.

My second shift of the evening I find myself hand steering.

“Can we engage the autopilot?” I ask.

“It’s not set up for this boat,” he says.

“What do you mean? I see it has its own switch on the breaker panel. It even has a name, PePe.”

“It’s not set up for this boat.”

“Man that’s really something we should have set up before leaving? Was it ever set up? Does it just not work?”

“I thought you were a hardcore sailor.”

By the next morning there is still no wind and the swell is building from the east. I’m too seasick to cook and there is nothing to eat that doesn’t require cooking besides fruit. By the third day we are still clawing our way out of the Gulf of Honduras. We are averaging between 2-3 knots. We have managed to come together enough to get some meals cooked and I’m trying to convince the captain we can’t make it all the way to Key West with the food situation as such. We have to stop in Mexico. We haven’t even reached the Gulf Stream or gotten parallel with Belize City yet, which was only 120 miles north of where we left. I don’t know exactly how many miles we have traveled because he’s not keeping track on the paper chart. It’s not my style of navigating, but I don’t fight him because I’m exhausted and hungry and plotting the coordinates seems difficult. We have the GPS and Navionics going. It’s his boat, I tell myself.

The wind and seas are building and are right on the beam. We are still moving along slowly. By evening the captain is also fed up with seasickness and not having the right food to eat and he agrees to plot the course for Cozumel, Mexico. This feels like a win. Soon there will be food! I start thinking about my friends in the keys that I’ll get to see when we make land fall. I think about my friends that I had made in Rio Dulce. But I can’t escape a sinking scared feeling that something bad has happened back home. That someone is in trouble and I write in my log that day that I just want to make it back home.

Moving along still at only 2-3 knots we are getting punished by the wind and waves. By midnight it is 35 knots, gusting 40. Any semblance of a structured watch schedule that I tried to create went out the window after the first night. Now, in what very much feels like a gale, we are only getting one to one and a half hours of sleep each. I start thinking about what I’ll do when I get back to shore to boost morale. We are pointed into the wind with a triple reef in the main sail with tiller lashed to leeward. The boat can’t get enough momentum to tack and falls off. We are shittily hove to until conditions worsen and we are getting rocket launched off of waves. I’m pretty scared of a knock down at this point and start reading the storm tactics book in my bunk while intermittently poking my head outside and regularly watching the AIS. For some reason I’m not seasick anymore, but it is too rough to cook. On my next off watch I wake up to the loud crash of a wave beam-on and the captain scrambling up from his bunk to look at the AIS. He begins to franticly call a ship. He was asleep on his watch.

“Norwegian Cruise Lines, Norwegian Cruise lines this is the small sailboat off your port bow I cannot adjust course do you see me, over.”

“This is Norwegian cruise ship,” the ship captain replies calmly. “I don’t see you on radar or AIS. Over.”

The captain flashes the spotlight out into the night.

“Oh my god,” the ship’s captain comes back, his voice no longer calm. “I see you. I am changing course.”

I look outside and see the cruise ship cross our bow eerily close moments later. If it was daytime, and there were people on deck, I could surely have seen them. There’s my nervous laughter again. Another waves crashes into our beam and sends us flying. The captain is thrown into the stove and knocks it off its gimble. There is potato soup everywhere. I can hear panic in his voice. I try to clean up the soup and remain calm. The ships captain comes back on the radio. The gusts are getting stronger. You can hear and feel it.

“How long have you been out here,” the ships captain asks. “It’s fifty knots right now. It’s kind of crazy that you guys are out here. Really kind of crazy.”

We ask him for a weather report and he only has one for the next six hours, which doesn’t show the wind letting up. We tell him that we will likely run down wind to Belize City, which is about fifty miles west to get inside the protection of the reef and then 25 more miles south to the channel into the city. He tells us he thinks this is a good idea. I give him our position and ask him to notify the Coast Guard of it once he is in radio communication, so that they know where we are just in case. He tries calling the coast guard but is out of range. He wishes us good luck.

We both look at each other and don’t know what to do. We discuss options. I suggest heaving to with the storm jib back winded as well as the triple reefed main. He says he’s tried it before and he can’t get the boat to heave to like this. So I suggest we add the sea anchor to that mix but he doesn’t want to hoist the storm jib. He begins to ready the sea anchor but doesn’t want to use it in conjunction with any sails. Running down wind under bare poles to Belize City is an option, but neither of us know how the boat will handle that. How much is too much wind or how big are too big seas to run down wind. We don’t know what kind of control we will have with the boat like that and worry we might end up on the reef. He drops the main and we deploy the sea anchor. It doesn’t work. We are still just drifting along with the wind and seas on our beam. We go on like this for an hour, maybe more. He is apologizing to me. He is praying. He is saying, “I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do.”

It’s going to be okay, I remember saying. But maybe it wasn’t out loud.

He decides to haul in the failing sea anchor (which only works when hove-to properly with your sails from what I understand). He’s not sure if he will be able to get it in or if he will have to cut it. He is wearing my foul weather gear and tells me I have to go up on the bow to help him.

“No,” I say calmly.

The deck has been a mess since we left. There are halyards, reefing lines, lines used for sheeting angles, all over the deck. Nothing has been coiled. The oars are placed hazardously. I have no foul weather gear to wear because he is using mine, and there is no reason to risk my life going up on the bow for something that doesn’t require two people. It was not my boat, and I hadn’t had an equal part sailing the boat, and I didn’t feel comfortable going forward in these conditions because of that.

He begins to scream at me.

“WHAT?! You’re not going to help me?”

“I’m going to help you,” I say. “I’m just not going up on the bow.”

The sea anchor is hauled in from the cockpit, around the winch. The captain is very tired from all the maneuvering in this sea state and I’m sympathetic to that, but need him to see us through. Because neither of us are familiar with the bare poles storm tactic, we don’t know if the weather is going to get worse, and there is a reef pass we are going to have to navigate we decide it’s best to press the emergency alert button on the SPOT tracker so the folks at home can notify the Coast Guard of our position, just in case.

“What’s the worst case scenario you think?” I ask him.

“I don’t know,” he says. “We lose the boat and have to get plucked off the reef.”

I press the emergency alert button.

Early on in his hand steering us down wind, bare poles, fifty knots, 10-15 foot waves he says, “Emily I’m getting sleepy.”

I pop my head out of the companionway and yell at him.

“No,” I yell over the wind, behind us now. “That isn’t an option. See us through. Do this for your kids. Pretend your kids are onboard.”

Every time a wave crashes into the boat I yell out to make sure he hasn’t been thrown overboard and is still awake. I don’t sleep down below. I am finally familiarizing myself with the chart, which has now gotten wet and is torn into pieces. I’m taping it back together and reading about navigating the channel that I hope we will pass through safely. I don’t sleep. At one point I hallucinate that the captain is one of my ex boyfriends and I feel safer for a moment. I only break down once when I spill powdered milk all over and I start to think about my parents and how worried they must be and I just want to get back to shore so I can tell them I’m okay. We are making insanely good time down wind. The seas and wind don’t seem to be increasing. Eventually I come outside and hold the tiller while he hoists the storm jib. The wind vane can be engaged again. It’s midday now and it’s been the night and morning from hell. We come into radio range and I hear ships talking about a sailboat in distress. They are talking about us. I get on the radio and tell them that we are okay. I talk to a few ships, then finally the coast guard. They have to send a plane to confirm our coordinates before they can officially call off the alert that was put out for our boat. The plane passes overhead of what I can only imagine was quite a sight.

I thank the Coast Guard profusely and immediately feel ashamed and embarrassed. Wondering if I made the right call to push the button. I cry alone inside the cabin feeling like a terrible sailor.

Coming into the channel the night of our fourth day underway things are mildly euphoric. We are drinking a beer, we’ve eaten a meal, the seas are flat even though the wind is still howling. We drop anchor off of a Belizean mangrove. We are still ten miles from Belize City where I get off the boat.

The day I leave the Captain is beside himself that he has to pay to check in so I can leave, sighting that I should be responsible for the fees because this was a mutiny. Meanwhile it costs me way more money for a hotel that evening, and a flight home the next day. A total of $600 I had to borrow from my dad, plus the time and money lost for being away from my boat. The captain contributes nothing to my expenses. The captain insists on keeping my SPOT tracker.

“I might need it,” I say. “I might have another delivery when I get back. Whose to say you will even give it back to me? You haven’t made good on any of your promises and you are under so much self imposed stress you can’t think of anyone outside of yourself.”

He then tells me to call his partner and kids and tell them I wouldn’t lend it to him. He tells me I’m heartless. An argument ensues. He yells at me for not doing the dishes. Says I’ve been a useless crew. We almost crash into the rocks. He says he will give me money for the month of the SPOT tracker I already paid for but he doesn’t. I help him tie up. I leave him the tracker. The immigration officer stamps my passport.

I leave him in his boat, tied to the dock in Belize City at a marina he couldn’t afford, crying over the fees he just had to pay to customs and the weather report he’d just gotten that predicted winds too strong to sail in for the next three days.

“Keep it together out there man,” I say and walk away.

I spent that evening in a hotel room crying at random intervals. I call his partner and tell her I left. I tell her I’m sorry. I recount the tale to my friends and parents. Wondering what I could have done differently. Wondering what I could have done better. Wondering if I’d made the right call pressing the emergency button. My captain friends try and offer kind words.

“Staying would not have been ‘doing better’.”

“You send the alert early, because later might be too late.”

“You did what you had to do. You didn’t know how it would end.”

One person asked me what I had learned, specifically what I had learned about the conditions in regard to my boat.

“Could your boat have handled that?” they asked.

It was hard to put into words how much I had taken from this situation. I learned to trust my gut. To leave when the captain first exhibits warning signs of being unfit for sea, to know proper storm tactics, to never ever leave the dock without knowing the boat and its systems stem to stern, to heed the advice of local sailors and to respect world cruising routes. To not take a passive role when it comes to weather routing and navigating, especially if you are having doubts about the captain. I also learned what an amazing land support team I have, that the Coast Guard is going to do absolutely everything they can to get you home safely, and to always have float and emergency contingency plans in place.

There are still questions left unanswered.

What if conditions had gotten worse?

What caused the forecast to go from 35 to 50 knots?

What should I have done differently?

As far as my boat and how it would have handled those conditions? I would have never gotten into that position. Distress or disasters at sea happen because of a series of events… or choices.

The pillow talk had come and gone by the time I’d arrived at the marina. The Capt. had apologized and assured me that he could of course take care of a pillow and said his oversights were due to stress. I apologized for saying “are you fucking kidding me,” one too many times. All was well enough. I was enjoying being in a foreign country, on foreign waters, and meeting many foreign sailors. Some good times were had and there were moments where morale was high and we functioned as a good enough team. I washed the boat (which was no easy feat having been at a dock in the jungle for nine months). I organized and cleared the cockpit. I did some painting. I cleaned up the Captain’s messes from projects and I tried my best to feed us with the meager provisions onboard at the time.

“I haven’t been eating,” was one of the first things he said to me when I arrived. “I haven’t been taking care of myself.”

I soon realized what he meant was he wanted me to do things like his laundry (which I didn’t do) and keep him fed (which I tried to do because I was also hungry) while he readied the boat. Any efforts I tried to take to be involved as crew were meant with serious backlash. I found myself laughing awkwardly, often, raising an eyebrow at his responses to what should have been the simple procedure of acquainting a new crew with the vessel.

There were things I wanted and needed to know before leaving; like the sail inventory, the reefing system, the route plan, ground tackle info, a run down on the electronics. We needed to discuss weather patterns, provisions and water for the trip, but none of this was possible. The captain would dismiss me, blatantly ignore me, and just generally be rude when I asked questions. He would respond as if his patience was on thin ice, as if I was being extremely annoying in my efforts to know the boat before setting off into the western Caribbean sea for several days at a time. I had dropped everything to come down there and help him for no monetary compensation and I was only concerned with my own safety and basic needs for survival at sea. He should have been acting gracious.

I eventually became worried about going to sea with him. I wondered how he’d handle an emergency. Luckily the boat was very simple and similar to mine, so I was able to observe things enough to get a sense of most of the systems, but there was something in my core that was very bothered by his inability to go over the boat together, and how he thought that it wasn’t important or necessary. I began to distrust his abilities as captain. Why should I have to be on my own learning his boat? It didn’t feel safe or right.

On the third or fourth day it was time to start thinking about untying from the dock. We still hadn’t provisioned and I still didn’t know which water tanks would contain filtered water and which would contain washing water. He had already made it clear that we would be provisioning on a budget, but then he told me with a staunch attitude that he would give me a certain amount of money and if I couldn’t provision within that then “oh well.” He said this in passing, walking past me carrying planks of wood for a sun awning that he never finished building. I took a breath, got up from my chair and followed him.

“Look,” I said as calmly as possible, “I’m not going to buy a bunch of outlandish items. It will cost what it is going to cost. I’m not going to go with you on the trip if this isn’t understood.”

He conceded, quickly. But the damage was already done. He’d tell me to get snacks, and then say nuts were too expensive. He told me not to worry about how much propane we had. He told me not to worry about the weather. He told me not to worry about water. He. Had. It. All. Under. Control.

I was pretty stunned. I was in a foreign country. I was starting to feel exhausted from having to fight for information and for what seemed like the most basic of needs. By the time he agreed to not capping the provisions budget, I was so anxious and exhausted I provisioned poorly with rice, vegetables, fruit, and eggs. Lots of them, but it all required massive energy to cook in an environment that was not only hostile due to its humidity, bugs, and punishing sun—but had become hostile between the two of us.

I contacted my friends back home. I talked to other people in the marina. I contacted the mother of his children. Some said I should leave, but I felt that if I left I was weak, I would return home with my head held in shame, that I was a failure. His partner at home told me he was responding to stress, that he was a good person, that he needed my help, but she would understand if I left. She talked to him and he apologized to me, again, in tears.

“I’m just so stressed out about money,” he said. “I just want to get home to my kids.”

I understood his predicament. I’d felt buried by the burden of my boat on more than one occasion. I know what stress, pressure, anxiety and depression can to do the mind. But it wasn’t an excuse for his behavior, and going to sea with a captain in that mental state seemed troublesome to me. At my weakest times emotionally, I didn’t bring someone else onto my boat. But I still wanted the sea time. I had come there with the intent to put to sea and damn it I was still going to do it.

I told him I was no longer doing this as a friend, and he’d have to compensate. I told him he’d have to pay me the amount it would cost for him to fly me home (a mere $200), and that he’d have to give me a solar panel and storm jib once we reached the United States. He was selling the boat anyway and had extras of each. Those were the terms. Otherwise I’d walk.

He pouted and said things like “this wasn’t our agreement,” and, “I don’t feel this is fair.” I made him shake my hand and look my in the eye. He then gave me a speech about how he was the captain. I just glared at him. I had no energy left to argue.

I felt better after asserting myself but nothing really changed. I tried to take a passive role. I still believed in the boat. When he said the route was solid I took his word for it. When he said the weather was good I believed him. He said there was one period where we might see strong 35 knot trade winds but they’d be on our stern quarter. I didn’t ask about the 35 knots, if it was part of regular trade wind behavior or some other weather system. I tried to treat this as a job with a bad boss, and as a practice for myself in trying not to be the captain. I convinced myself that was a good idea. I had managed to piece together a float plan to inform my contacts back home but left the rest to him.

Things continued to deteriorate and by the time we reached the bay where the sail repair and rigging shop was located up the river, we weren’t really speaking. When a young, dreadlock sailor girl tied us up to the riggers dock and looked at me to say, “What a beautiful little boat you have here.”

I quickly said back to her, arms crossed, “It ain’t my boat.”

We took an immediate liking to each other. She was at the dock refitting her classic wooden sailboat and works as a charter captain in Belize. I told her everything. She tried to rationalize it.

“You’ve already decided you’re staying, right? He’s just really stressed out. That’s not an excuse for his behavior but you trust the boat and he got down here, didn’t he? Just treat it as a job like you said. You need a ride back to the state’s anyway and you said you’d rather go by boat. Get your sea time. Get the items you negotiated. And get off the boat.”

After the rigger went up the mast I pulled him aside and told him briefly the scenario. He said the rig and sails were solid. That the captain was not an idiot, he was just nervous.

The folks at the dock, all sailors with a keen local knowledge, tried to tell the captain to stay inside the reef for the first 150 miles. It would be easier to make time before picking up a fair current with the Gulf Stream, but the captain wanted to go offshore the entire way.

The night before we were outbound to sea I went to the bar with my new friends and had a conversation with one of saltiest old salts I’d ever met. I started to ask him about storms.

“You don’t just get ‘caught’ in a storm,” he said. “If the captains not an idiot, he’ll have looked at the weather before going. He got down here didn’t he? You said you trust the boat. If you stay inside the reef to Belize City you pretty much pick up the gulf stream parallel with the pass .”

“Yeah I trust the boat,” I said. “Yeah he got down here. Yes he’s looked at weather. But he doesn’t want to stay inside the reef. He wants to go offshore the whole way. He’s already been told to stay inside the reef by local sailors.

“Well,” he said in his Australian accent, fifty years experience at sea, “Unless you want to get in a big, dangerous fight at sea, don’t tell him what to do when you’re out there. Treat it as a job, and get home.”

They say you don’t really know someone until you sail with them on a voyage on a 28-foot-boat. Or until you’re at the dock, getting ready to go on a voyage on a 28-foot-boat. They say that disasters at sea happen because of a series of events that lead up to them. Or a series of choices you make if you’re the captain or the owner of the vessel. Or a series of choices someone else makes if you’re the crew.

I was not in a disaster at sea. Obviously, I am here right now to tell the tale. But the nature of the distress I experienced happened that way; in a series of events, or a series of choices. Choices made by someone other than myself, because I was the crew.

The intended voyage was Rio Dulce, Guatemala, to Key West, FL on a 28-foot Pearson Triton. The boat was solid, this much I knew. Extensively outfitted for blue water. The captain had successfully made his way from the East Coast to the Rio with his young family in tow enjoying the foreign ports, sailing friendships, and beautiful scenery along the way. The captain was known for being cautious, conservative, and doing everything to a T. There was really only one incident the entire way down where their weather forecast in Cuba was wrong and they experienced 30 knot winds and a wind over tide in the Gulf Stream during a 24 hour passage. The boat and crew made it through no worse for ware. I knew the captain personally and looked up to him for the work he had done to my boat’s sister ship.

The return trip was going to be a bit different. No family. More of a mission. A mission I felt prepared for, because I trusted the boat and the captain. We would go offshore as much as possible, with only one or two stops as seen fit at the time. He would pay all of my expenses (which were very minimal because a flight to Guatemala and food were very cheap). To compensate for my actual time spent sailing, which actually was costing me money because I’d be leaving my unfinished boat accruing fees in a boatyard, he was supposed to help me work on my boat and deliver some much needed spare gear he had. This was to happen when he dropped his trailer off at the boatyard he intended to haul out in, which was right near my boatyard.

He never brought down the trailer, and thus never helped me work on my boat before leaving like he’d said. It was okay. Time gets away from you. I understood. I still wanted the sea time. I still trusted the boat and him. Then he didn’t have time to send the gear he’d promised for my boat, but he had time to send me two pounds of Pink Himalayan salt for the trip for me to carry in my luggage, and I had time to find him (us really at this point), a gimbaled stove from the used sailing shop which I paid for and also had to transport to Central America.

He then informed me that he had left his SPOT Tracker (a personal GPS Satellite tracking device that can be used for emergency communication) in the mountains of Guatemala, or was it California, or North Carolina, leaving the boat with no offshore emergency communication. Luckily I had my own SPOT device, which I had planned to activate anyway, but it was an older generation model that I’d been given for free and hadn’t used yet. Then he wanted me to buy him the waste and oil discharge placards required by the U.S. Coast Guard, or take the ones of my boat and let him use them. I only had two days between the last delivery I was on and leaving for this one. I was running around trying to pack, square my boat away, get any last minute supplies I would need, and activate and test my emergency communication device. I didn’t have time to go to buy them and I wasn’t going to peel stickers off my boat for him. I ignored his request for the placards.

I asked him how the weather patterns were looking. He replied by saying he hadn’t been looking at the weather, since he’s been so busy working on the boat, and he saw no point in looking at the weather until the boat was ready to go.

He then told me to bring my own pillow.

I didn’t have room in my luggage because I was carrying gear for him, my foul weather gear and personal safety equipment. He was starting to sound a bit unprepared and I was flying there the next day. Would I not have a pillow for this entire voyage? Was he so broke he couldn’t buy me a pillow in Rio Dulce, a busy little town where the U.S. dollar goes far? Was this indicative of what was to come?

I called my friend the night before leaving and asked “is this voyage ill fated?”