When I think of the East Coast the first thing that comes to mind is not a wild landscape. Yes, there are beautiful ocean beaches, historic lighthouses, protected national seashores, and a variety of other delights ashore. But the majority of shoreline is privately owned. I think of the east coast as the place I grew up. A good place to buy, fix, and practice seafaring aboard small sailboats. As a place you have to sail past to get to the islands. But never as a place to travel to. It is not the land in itself that interests me. It is the sea. It is being out of sight of land.

Coming back to shore here is merely a means to an end as my boat is a continuous work in progress, not quite ready to be at sea for longer than a few days. It is distant landfalls with far less population that intrigue me, not the coastal U.S. cities. Sometimes I wait weeks for a small passage window, anchored in some town I’d never chose to visit on purpose. Where there are few public landings and grocery stores are miles outside of town down four lane highways. Sometimes I get lucky and I can see a rail yard from the lawn of the public library and watch freight trains roll by while using the WiFi. Other times, there are mates around. I’ve been up and down this coast enough to have friends almost wherever I go, but not always.

From sea the coastline can look almost perverse. The abandoned Ferris wheels of the New Jersey Coast, the sky scraping condos of Miami Beach, accompanying tributaries marked endlessly by mansions, water towers, beach houses, second, third, and fourth homes. It’s as if the only reason they stopped building is because they ran out of land. They ran into the water. It like civilization is just perched precariously and ready to crumble into the ocean. Like an apocalyptic daydream.

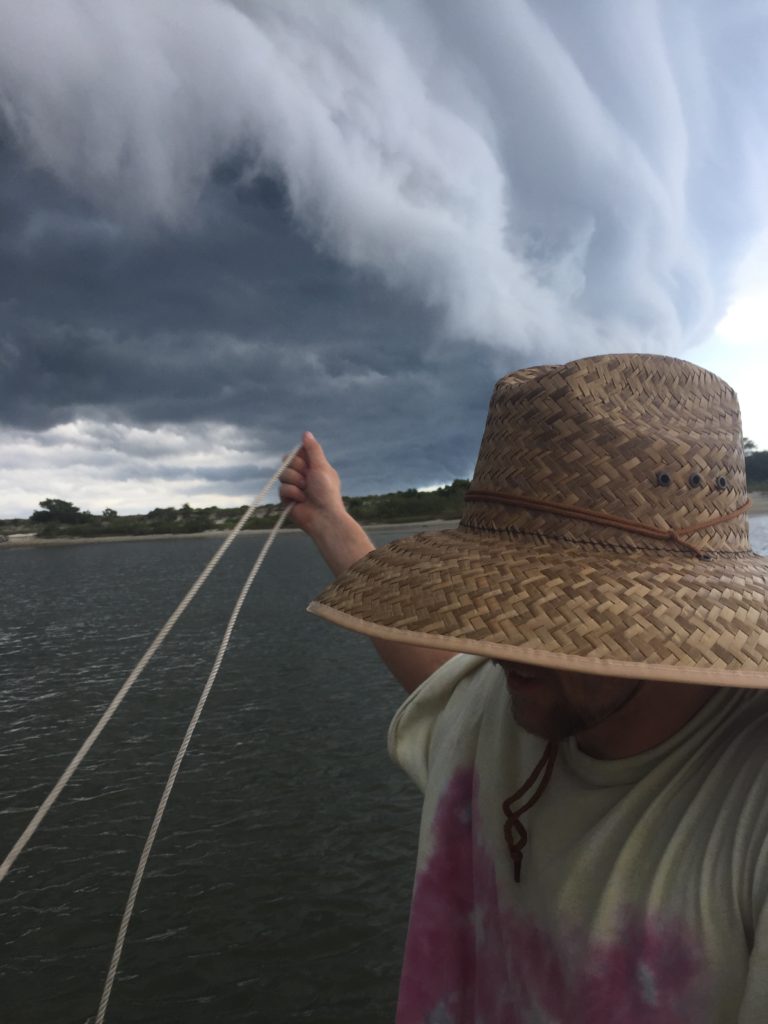

The wind can be a challenge as well.

The East Coast is killing my soul a little.

But I do it for you, Atlantic.

[email-subscribers-form id=”1″]